Regia / Director: Vittorio De Sica, 1948

Vediamo Maria incorniciata dalla porta della cucina, il suo grembiule sgualcito, il suo sguardo di profonda preoccupazione e determinazione. Va in camera da letto, dove Antonio siede piegato sul letto, sconfitto dal suo dilemma.

We see Maria framed in the kitchen door, her rumpled apron, her look of deep concern and determination. She goes into the bedroom, where Antonio sits bent over on the bed, defeated by his dilemma.

Inginocchiandosi, Maria strattona il cassetto inferiore della cassettiera, che si apre un po' a fatica. Tira fuori un pacco ben incartato.

Fuori dalla finestra, le forme degli archi e dei vestiti appesi costituiscono una composizione astratta, splendidamente equilibrata.

Kneeling down, Maria yanks at the bottom drawer of the dresser, which sticks a little as it opens. She pulls out a neatly wrapped package.

Outside the window, the shapes of arches and hanging clothes make up an abstract composition, beautifully balanced.

Gettando il pacco sul letto più piccolo, strattona il braccio di Antonio. "Togliti, Anto’!"

Tossing the package on the smaller bed, she tugs at Antonio’s arm. “Get out of the way, Anto’!”

Tira via le coperte dall'altro letto e le getta da parte. Poi toglie le lenzuola e le raccoglie in un fagotto.

She pulls the blankets off the other bed and tosses them aside. Then she strips off the sheets and gathers them into a bundle.

Con le lenzuola in braccio, si volta per andarsene.

"Ma che fai?" chiede Antonio, con aria confusa.

"Si può dormire pure senza lenzuola, no?"

With the sheets in her arms, she turns to leave.

“But what are you doing?” Antonio asks, looking bewildered.

“We can sleep without sheets, can’t we?”

In cucina, butta le lenzuola in terra e si prepara a lavarle per il banco dei pegni. Per questo deve usare la preziosa acqua che ha appena trascinato dalla fontanella pubblica.

In the kitchen, she tosses the sheets to the floor and prepares to wash them for the pawn shop. For that, she has to use the precious water she’s just dragged from the public fountain.

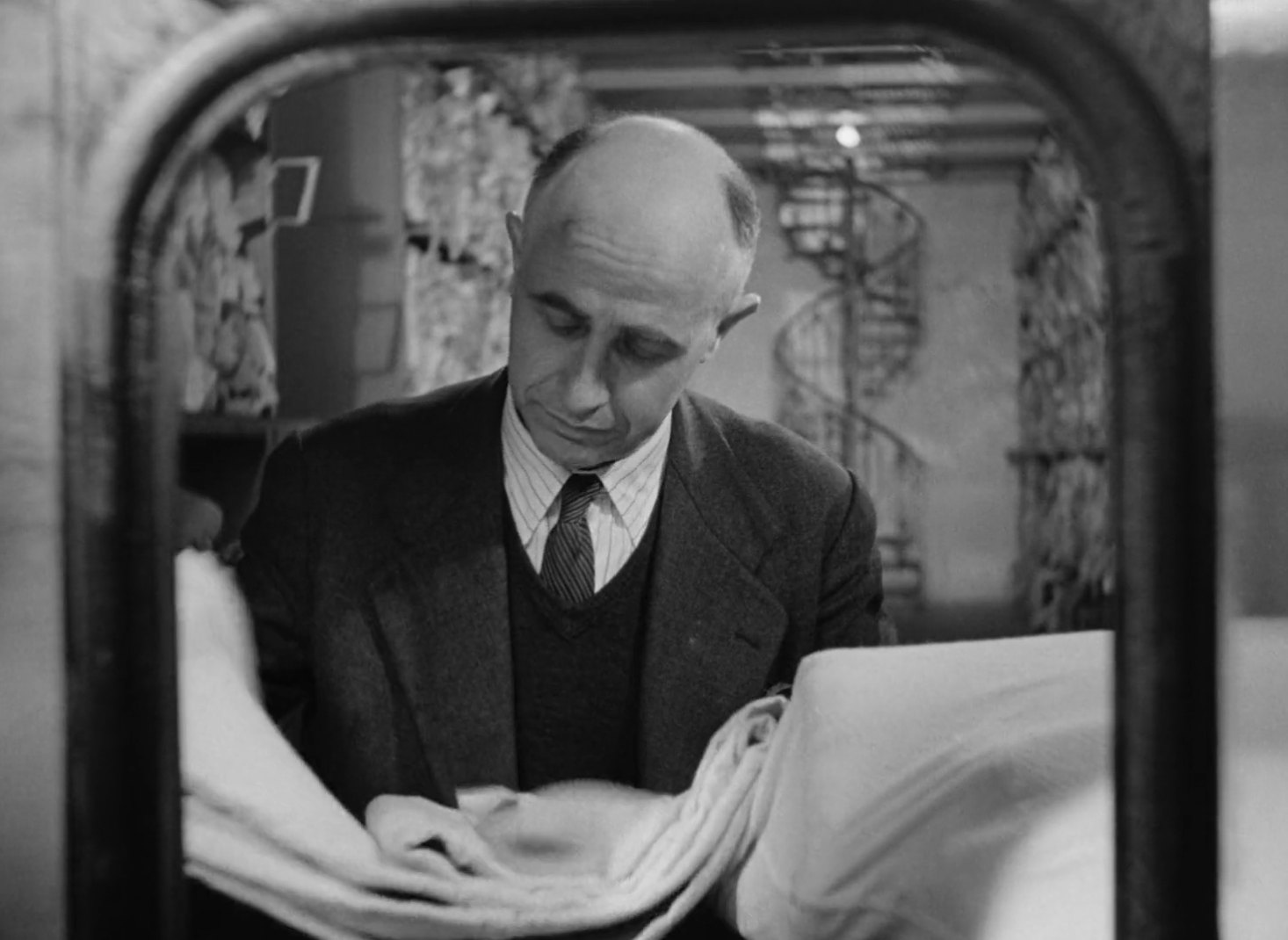

Al banco dei pegni, Maria fa passare il pacco attraverso la piccola finestra. "Sono lenzuola" – dice – "Sei!" L’addetto, un uomo calvo in camicia e cravatta ordinate, le esamina con calma e attenzione.

At the pawnshop, Maria jams the package through the tiny window. “They’re sheets,” she says. “Six!” The clerk, a balding man in a tidy shirt and tie, examines them calmly and carefully.

Lei si sporge dalla finestra. "Sono di lino e cotone, roba buona, da corredo". Dietro di lei, vediamo i volti di altre persone che aspettano con ansia di incassare qualcosa dai loro pochi averi.

"Sono usate", commenta l’addetto.

She leans in through the window. “They’re linen and cotton, good stuff, like from a trousseau.” Behind her, we see the faces of others waiting anxiously to cash in their scant possessions.

“They’re used,” the clerk comments.

"Quattro pezzi sono usati. Due sono nuovi". Lei lo guarda speranzosa.

“Four pieces are used. Two are new.” She looks at him hopefully.

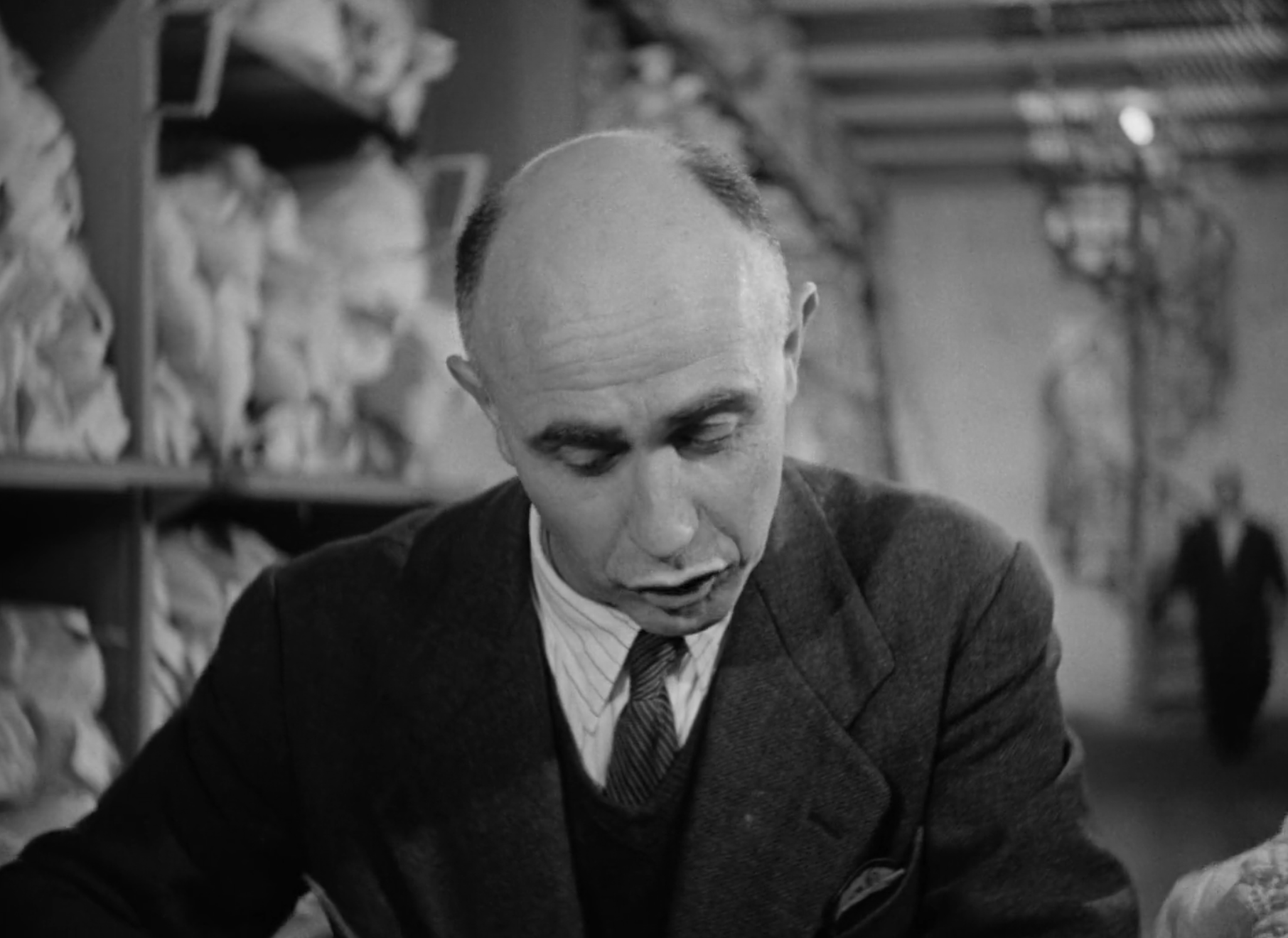

Lui piega le lenzuola: "Settemila". Dietro di lui, vediamo pile di scaffali pieni di lenzuola. Sulla parete in fondo sale una scala a chiocciola.

"Settemila?"

He folds the sheets: “Seven thousand lira.” Behind him, we see stacks of shelves stuffed with sheets. At the back wall, a spiral staircase ascends.

“Seven thousand?”

Lei guarda Antonio, che si affaccia allo sportello. "Non si potrebbe fare un po' di più?"

She looks over at Antonio, who pokes his head into the window. “Couldn’t you make it a bit more?”

"Sono usate". L'uomo scuote la testa, sorridendo come se fosse evidente. Dietro di lui, fuori fuoco, vediamo ancora la sua vasta scorta di lenzuola.

“They’re used.” The man shakes his head, smiling as if it’s self-evident. Behind him, out of focus, we still see his vast stockpile of sheets.

I volti dei Ricci sono intrappolati nella piccola apertura quadrata. L’addetto incombe su di loro.

The Riccis’ faces are trapped within the tiny square window. The clerk looms over them.

"Settemila e cinquecento", concede l'uomo. Maria ha impegnato le preziose lenzuola della sua dote. In una storia che sarà piena di burocrati e funzionari indifferenti, quest'uomo sembra almeno riconoscere l’umanità della coppia.

Maria sorride con gioia.

“Seven thousand, five hundred, the man concedes. Maria has pawned the treasured sheets from her dowry. In a story that will be filled with indifferent bureaucrats and officials, this man at least seems to recognize the couple’s humanity.

Maria smiles brightly.

"Nome?" chiede l’addetto.

"Ricci Maria".

Secondo lo stile italiano di quegli anni per le situazioni burocratiche, lei dà prima il suo cognome. Fornisce anche il suo indirizzo.

“Name?” the clerk asks.

“Ricci, Maria.”

In the Italian style of the time for bureaucratic situations, she gives her last name first. She also provides her address.

L’addetto le consegna un foglio di carta e poi conta le banconote, posandole sul bancone: "Uno, due, tre..." Sembra tranquillamente soddisfatto della transazione.

The clerk hands her a slip of paper and then counts out the bills, setting them on the counter: “One, two, three…” He seems quietly pleased with the transaction.

Lei prende le banconote e fa un gran sorriso all'uomo. "Grazie".

"Buongiorno".

She takes the bills and flashes a big smile at the man. “Thank you.”

“Have a good day.”

I Ricci se ne vanno e alla finestra appare un’altra faccia preoccupata: un uomo dai capelli bianchi che spera di impegnare il suo binocolo.

The Ricci's leave, and another troubled face appears at the window: a white-haired man who’s hoping to pawn his binoculars.

Antonio si sposta verso un altro sportello del banco dei pegni, con un addetto vestito da meccanico, con camicia e tuta da lavoro sgualcite. Sullo sfondo, delle biciclette pendono dal soffitto, un intreccio di curve e linee rette.

Sorridendo con trepidazione, Antonio consegna il biglietto di ritiro. "È una bicicletta".

Antonio moves to another window in the pawnshop, with a clerk dressed like a mechanic, in a crumpled shirt and overalls. In the background, bicycles hang from the ceiling, a web of curves and straight lines.

Smiling with anticipation, Antonio hands over his claim ticket. “It’s a bicycle.”

L'uomo esamina il foglietto e poi sfoglia gli articoli del suo registro. Alza lo sguardo: "Seimila e cento".

The man examines the slip of paper, and then scans through the items in his register. He looks up: “Six thousand, one hundred.”

Il sorriso di Antonio si spegne. "Perché?"

"Gli interessi. Siamo al trentuno".

Antonio’s smile fades. “Why?”

“Interest. It’s the thirty-first.”

"Ecco". Di nuovo raggiante, Antonio consegna il denaro. Senza sorridere, l’addetto legge il biglietto di ritiro.

“Here.” Beaming again, Antonio hands the money over. Without smiling, the clerk reads the claim ticket.

Mentre cerca tra le file di bici, Antonio gli dice: "È la Fides. Vicino a quella rossa".

Una fila di ruote di bicicletta attira lo sguardo verso il fondo dell'inquadratura, dove l’addetto dice stancamente: "Lo so, lo so".

As he searches through the rows of bikes, Antonio tells him, “It’s the Fides. Next to that red one.”

A row of bicycle wheels draws the eye to the back of the shot, where the clerk says wearily, “I know, I know.”

Mentre recupera la bicicletta, passa un altro impiegato, con la schiena rigida e in giacca e cravatta. Porta le lenzuola dei Ricci.

As he retrieves the bike, another employee, stiff-backed in a suit, passes through. He’s carrying the Riccis’ sheets.

Antonio osserva l'uomo che si dirige verso una scaffalatura con alti ripiani che ospitano lenzuola impegnate. Tenendo le lenzuola impacchettate in una mano, l'uomo si arrampica con perizia sugli scaffali, a una decina di metri d'altezza. È evidente che l'ha fatto molte volte.

Antonio segue l'uomo con lo sguardo.

Come sottolinea Charles Leavitt IV nel suo illuminante libro Italian Neorealism: A Cultural History le lenzuola dei Ricci, una volta sistemate su uno scaffale, non sembrano diverse dalle migliaia di altre lenzuola impilate lì. Ma per i Ricci hanno un valore speciale. Vedremo questo tema più volte: Antonio è solo un uomo, la cui storia non ha importanza per nessuno al di fuori della sua famiglia. Per noi è un individuo, perché lo conosciamo. Ma la sua storia è uguale a quella di molte migliaia di altri.

Antonio watches the man walk to a storage area with tall shelves bearing pawned sheets. Holding the bundled sheets in one hand, the man expertly climbs up the shelves, some thirty feet in the air. Clearly, he has done this many times.

Antonio follows the man with his gaze.

As Charles Leavitt IV points out in his illuminating book, the Riccis’ sheets, once set on a shelf, seem no different from the thousands of other sheets stacked there. But, to the Riccis, they have special value. We’ll see this theme again and again: Antonio is just one man, whose story doesn’t matter to anyone outside his family. To us, he is an individual, because we know him. But his story is the same as many thousands of others.

FINE PARTE 3

Ecco Parte 4 of this cineracconto. Subscribe to receive a weekly email newsletter with links to all our new posts.