Regia / Director: Antonio Pietrangeli, 1965

Vista dal basso, Adriana cammina da sola davanti all’antica facciata del Duomo di Orvieto, con la brezza che le scompiglia il foulard. I suoi tacchi ticchettano sul marciapiede.

Seen from below, Adriana walks alone past the ancient facade of the Orvieto Cathedral, the breeze blowing her scarf. Her heels click on the sidewalk.

Sentendo dei passi, Adriana si guarda intorno nervosamente. Cammina, poi si ferma di nuovo. Ma è solo la sua ombra che la segue.

Hearing footsteps, Adriana looks around nervously. She walks on, then stops again. But it’s only her shadow following her.

Con la cattedrale che la sovrasta, si guarda di nuovo alle spalle. Al ticchettio delle sue scarpe sul marciapiede si è aggiunto quello di qualcun altro.

With the Cathedral towering above her, she looks over her shoulder again. The clicking of her shoes on the sidewalk has been joined by someone else’s.

Mentre scende una rampa di scale, vediamo l'altra persona: Bietolone. Non sembra avere fretta.

While she descends a flight of stairs, we see the other person: Lunk. He seems in no hurry.

Mentre lui cammina sotto un portico, Adriana sbuca dal suo nascondiglio. "Ah! È lei!" Sembra sollevata.

"... ’sera..." Lui è perplesso.

As he walks under a portico, Adriana pops out from her hiding place. “Ah! It’s you!” She sounds relieved.

“... ‘evening...” He’s puzzled.

Lei prosegue, ma si volta e dice: "Mi sono spaventata!"

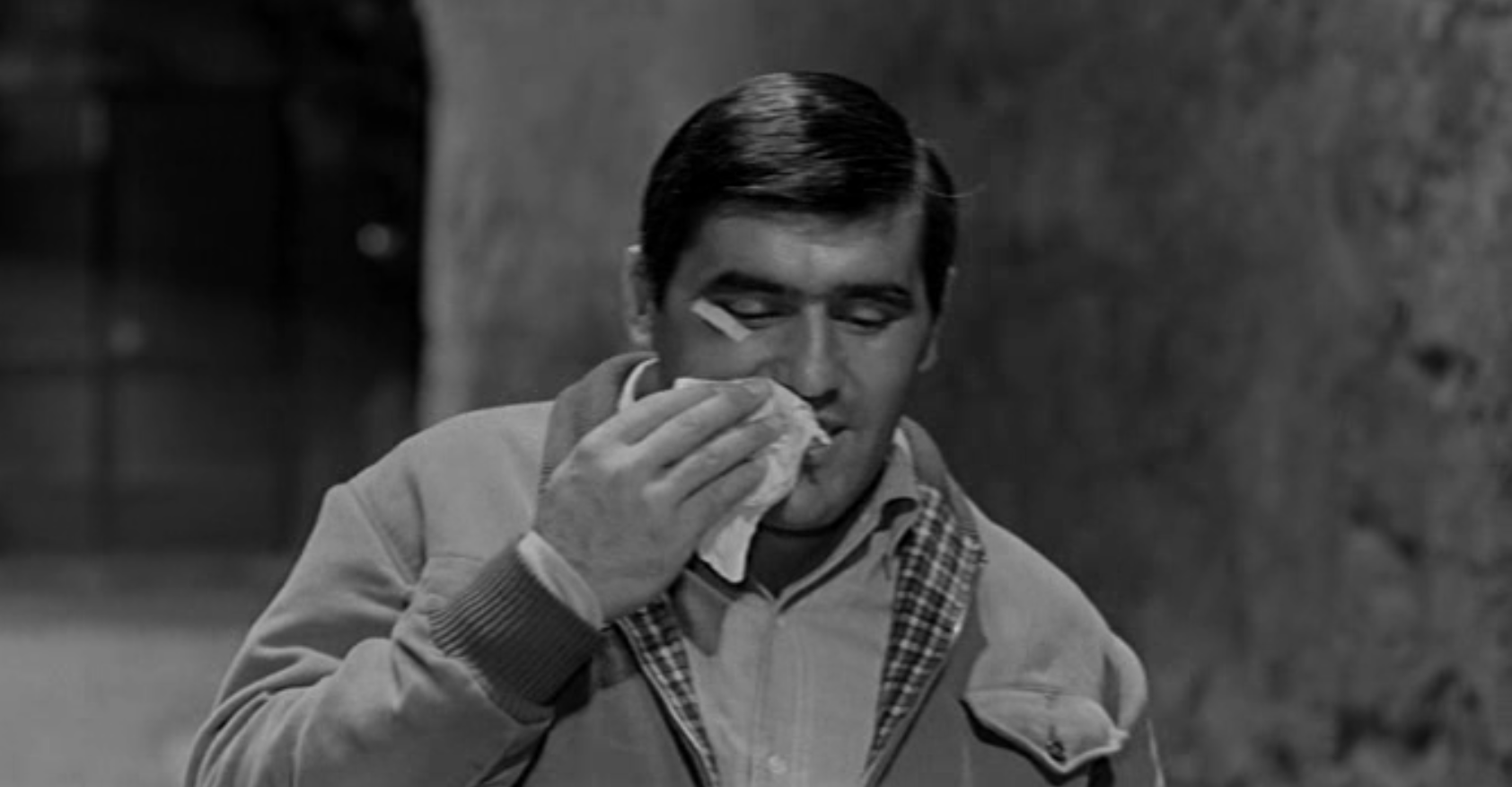

Lui ha un fazzoletto premuto sulla bocca.

Voltandosi di nuovo, lei chiede: "Le fa molto male?"

"Hmm?"

She walks on, but turns and says, “I got scared!”

He has a handkerchief pressed to his mouth.

Turning again, she asks, “Does it hurt a lot?”

“Hmm?”

"Qui", dice lei indicando.

"No, no, no! Ormai ci sono abituato".

“Here,” she says, pointing.

“No, no, no! I’m used to it by now.”

Lui la riconosce: "Lei era in sala, mi pare”.

"Sì, e facevo il tifo per lei".

He recognizes her: “I think you were in the hall.”

“Yes, and I was rooting for you.”

"E ho urlato un sacco di volte: ‘Dai, Bietolone!’ ‘Forza, Bietolone!’" Si gira verso di lui. "Si chiama così, vero?"

"No, mi chiamo Ricci. Ricci Emilio.* Mi chiamano ‘Bietolone’ perché dicono che sono lento". Timido, non ha ancora stabilito un contatto visivo.

*Come abbiamo visto in precedenza, gli italiani forniscono il loro cognome per primo in situazioni formali. Il fatto che Ricci lo faccia qui suggerisce la distanza sociale che sente tra sé e Adriana.

“And I shouted so many times: ‘Come on, Lunk!’ ‘Give it to him, Lunk!’” She turns to him. “That’s your name right?”

“No, my name is Ricci. Ricci Emilio.* They call me ‘Lunk’ because they say I’m slow.” Shy, he’s yet to make eye contact.

*As we’ve seen before, Italians provide their last name first in formal situations. That Ricci does so here suggests the social distance he feels between himself and Adriana.

"Beh... Però anche lei ha dato un sacco di bei pugni a quello lì, eh?”

"Sì, ma… Mi ricordo solo quelli che ho preso", dice lui con imbarazzo, gli occhi bassi.

Lei scoppia a ridere, con la mano guantata sulla bocca, e anche lui ride.

“Oh… But you landed a lot of great punches on him, you know!”

“Yes, but… I only remember the ones I got,” he says sheepishly, eyes lowered.

She bursts into laughter, with her gloved hand over her mouth, and he laughs too.

A una fontana d'acqua, Ricci si sciacqua il viso ferito, mentre le campane della chiesa suonano in sottofondo. Questa inquadratura fa venire in mente il marinaio de Le quattro giornate di Napoli (Nanni Loy, 1962), innocente e puro di cuore, che si sciacqua il viso alla fontana prima di essere arrestato dal soldato tedesco.

At a water fountain, Ricci rinses his wounded face, as church bells ring in the background. This shot brings to mind the sailor from The Four Days of Naples (Nanni Loy, 1962), innocent and pure of heart, rinsing his own face at the water fountain before he’s arrested by the German soldier.

Seduta vicino, Adriana chiede: "Le piace tanto la boxe? Insomma, ci vuole una gran passione per farsi ridurre in quello stato, no?"

"Passione c'è, ma anche il guadagno. Stasera mi hanno dato 80.000 lire. Guadagno più con la boxe che con il mio lavoro".

Sitting nearby, Adriana asks, “Do you really like boxing? I mean, it takes a great passion to let yourself get reduced to that state, doesn’t it?”

“Passion, sure. But there’s the earnings, too. They gave me 80,000 lira tonight. I make more by boxing than at my regular job.”

"Che lavoro fa?"

Lui abbassa lo sguardo, imbarazzato. "Per adesso il facchino al mercato, ma... tra poco apro un negozio di frutta, e ci vogliono un sacco di soldi. Così, quando capita un incontro..."

“What do you do?”

He looks down, embarrassed. “I’m an errand boy at the market for now, but… I’ll open a green grocer’s soon, and that takes a lot of money. So when a match comes along...”

Camminando di nuovo, Adriana commenta: "Io credo che per andare bene un pugile dovrebbe sempre scegliersi un avversario più debole di lui, no?”

"Strucchi, il mio avversario, ha fatto così!"

Lei ride, mentre un treno fischia.

Walking again, Adriana comments, “I think that to do well, a boxer should always choose a weaker opponent than himself, shouldn’t he?”

“Strucchi, my opponent, did just that!”

She laughs, as a train whistle blows.

Alla stazione, in attesa di un treno per Roma, lei si avvicina per toccargli il viso ferito. "Ahi!" Lui indietreggia.

"Fa male, eh? Certo che è bello gonfio".

At the station, waiting for a train to Rome, she reaches over to touch his wounded face. “Ay!” He recoils.

“It hurts, huh? It sure is good and swollen.”

Due impiegati delle ferrovie passano parlando.

"È un truffa bella e buona! Pago per quindici anni fior di quattrini, e quando mi si caria un dente quelli del fondo sanitario mi dicono: ‘Se te lo fai togliere, è gratis. Se te lo vuoi curare, devi pagare'."

"E tu l’hai tolto?"

"Certo".

Two railroad employees walk by, talking.

“It’s an outright scam! I pay big bucks for fifteen years, and when I get a cavity, the people from the health fund tell me: ‘If you get it taken out, it’s free. But if you want it treated, you have to pay.’”

“So you had it removed?”

“Of course.”

Ricci commenta: "Invece secondo me è una cosa molto utile".

"Che cosa?"

"Il fondo sanitario".

"Ah..." Lei distoglie lo sguardo, improvvisamente annoiata.

Ricci comments, “I think it’s very useful.”

“What is?”

“The health fund.”

“Ah…” She looks away, suddenly bored.

Lui aggiunge: "Mia sorella ha fatto due gemelli senza spendere una lira!"

Lei risponde: "Anch'io ho una sorella!"

"È sposata?"

"Non lo so..." Fa una pausa, pensierosa.

He adds, “My sister had twins without spending a lira!”

She replies, “I have a sister too!”

“Is she married?”

“I don’t know…” She pauses, pensive.

"Oh, non credo. No, forse no. È più piccola di me".

“Oh, I don’t think so. No, maybe not. She’s younger than me.”

Tornano i ferrovieri. "Senza l'anestetico me l’ha levato! Se volevo l'anestetico lo dovevo pagare io”. Indica la bocca aperta. “Ecco qua! Lo vedi che mi manca?"

"Sì, c'è un buco!"

"Ma sai che gli ho detto? Allora, se mi faccio male a una gamba, voi invece di curarmela, me la tagliate?"

The railroad workers return. “He took it out without anesthetic! If I wanted anesthetic I would have had to pay.” He points to his open mouth. “There it is! See that I’m missing it?”

“Yes, there’s a hole!”

“Know what I told him? So, if I hurt my leg, would you amputate instead of treating it?”

"La sua ragazza è contenta che lei fa la boxe?"

"Non ce l’ho la fidanzata".

“Is your girlfriend happy that you’re a boxer?”

“I don’t have a girlfriend.”

Sorridendo, apre la valigetta. All'interno è incollata la fotografia di una bella donna.

Smiling, he opens his briefcase. The photograph of a beautiful woman is taped inside.

"Bellina! Ha visto che ce l’ha?"

Lui chiude la valigetta. "A lei lo posso dire. L’ho vista nella vetrina di un fotografo e... me la sono fatta dare".

"E non sa neanche chi è?"

Lui scuote la testa, chiudendo la valigetta. Adriana gli sorride con affetto.

“She’s pretty! See, you do have one!”

He closes the case. “I can tell you. I saw that picture in a photographer’s window and… I had them give it to me.”

“And you don’t even know who it is?”

He shakes his head, closing the case. Adriana smiles at him fondly.

Sentendo un annuncio, Adriana dice, per metà a Ricci e per metà a se stessa: "C'è un treno per Pistoia..."

Hearing an announcement, Adriana says, half to Ricci, but half to herself, “There’s a train to Pistoia…”

Lui commenta: "Ma non doveva andare a Roma?"

"Sì, ma invece di aspettare altre due ore potrei... È tanto che non ci vado...".

He comments, “Weren’t you going to Rome?”

“Yes, but instead of waiting another two hours, I could… It’s so long since I’ve been there…”

È così: sta tornando a casa. Si alza di scatto e corre verso il treno. "Ma si, è meglio, vado a Pistoia!"

That’s it: she’s going home. She leaps up and runs toward the train. “Yes, it’s better, I’m going to Pistoia!”

Voltandosi, torna di corsa da Ricci. "Grazie della compagnia!" Lo bacia sulla bocca.

Turning, she runs back to Ricci. “Thanks for the company!” She kisses him on the mouth.

Poi si ricorda della sua ferita. "Scusi, il labbro, mi dimenticavo! Ciao, Biet— Arrivederci, Emilio!" e se ne va.

Then she remembers his wound. “Sorry, the lip, I forgot! Bye, Lu– Goodbye, Emilio!” and she’s gone.

Da fuori campo, lei urla: "E non si faccia rovinare, eh!”

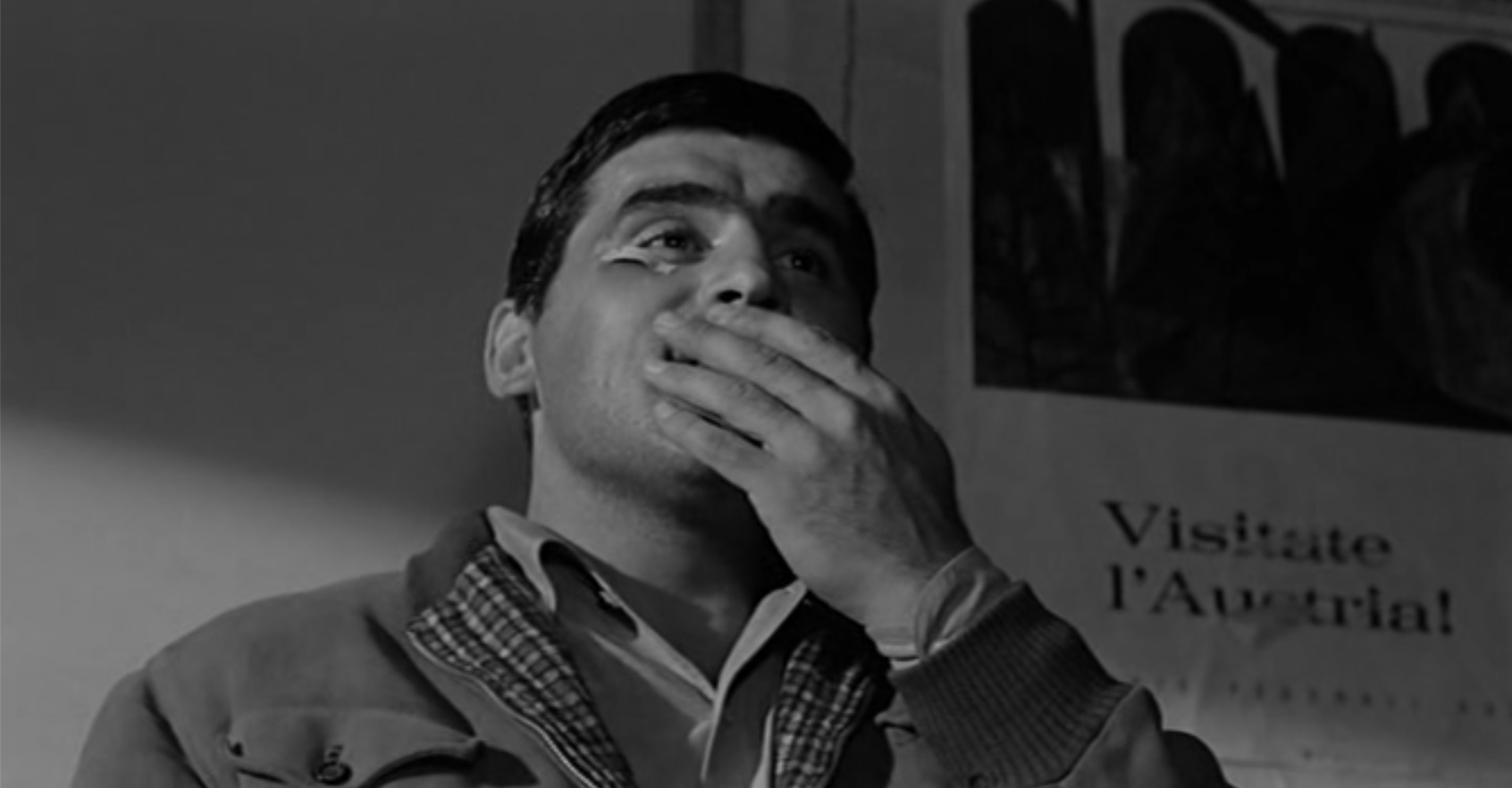

Lui la segue con lo sguardo, come in un sogno, e tocca le labbra che lei ha baciato, mentre il treno parte.

From off-screen, she calls, “And don’t let them ruin you, okay?”

He gazes after her as if in a dream, and touches the lips she kissed, as her train departs.

FINE PARTE 8

Ecco Parte 9 of this cineracconto! Subscribe to receive a weekly email newsletter with links to all our new posts.